A crossroads of cultures defines this beleaguered city just inland from the Adriatic coast in the southern part of Bosnia-Herzegovina

Edin “Pelko” Pelkovic recalls November 9 1993 – the day the Serbians bombed Mostar’s medieval Stari Most Bridge into the River Neretva – like it happened yesterday. “I’m not ashamed to say I wept like a baby. I think every Bosnian alive cried that day.”

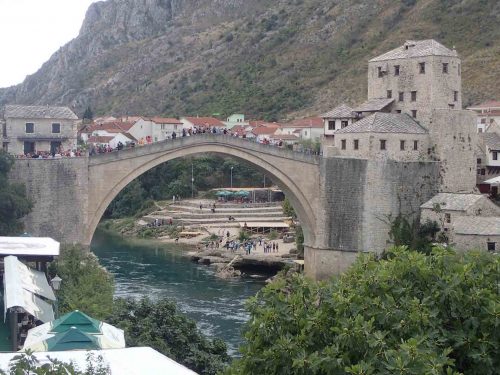

Understandable when you consider that the Old Bridge – constructed on the orders of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent – dated back to 1566. The swooping stone arch of the original walkway was rebuilt in 2004 from rubble hauled out of the river, and declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in Durban on July 17 2005. Why the bunny chow capital was chosen for this honour, I can’t say.

Today, daredevil divers fling themselves off the Stari Most parapet, dropping 20m into the Neretva’s icy waters for thrills, chills, and cash tips. You thought bungee jumpers were brave? Pah!

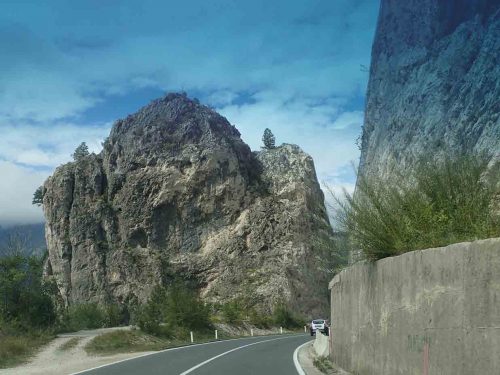

The road to Mostar is paved with narrow hairpin bends flanked by shrines and random stalls selling honey, homegrown tobacco, and vegetables. With more mountains than Switzerland and a burgeoning wine industry – ironic for a Muslim country, but that’s Bosnia-Herzegovina for you – the views change from castle ruins to bombed out farmhouses, fruit trees, tunnels, rivers and streams.

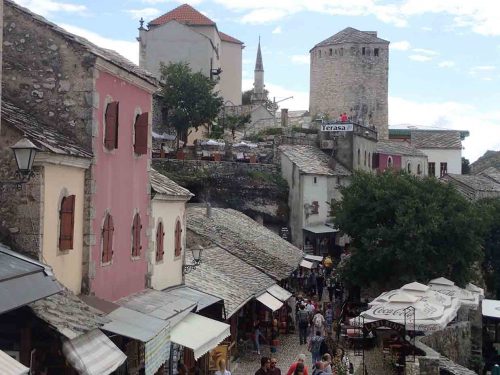

Refined by the minarets of many mosques rising like middle-fingered salutes to the Serbians, Mostar lurks in a birch-forested valley. Across the river, twice the length of the tallest minaret, stands the Croats’ new Catholic Church spire. And on the hilltop high above the town, a cross heralds what might be an uneasy truce, but time will tell. Things were pretty peaceful while we were there, and the same in Sarajevo.

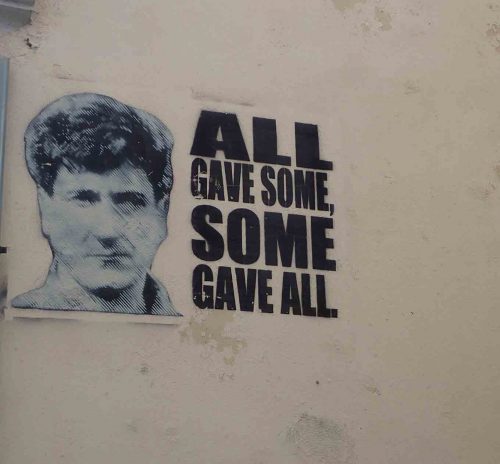

Orthodox Serbs, Catholic Croats, and Muslim Bosniaks lived here in harmony before war broke out in 1992. Croats and Bosniaks forced out the Serbs before turning their guns on each other and the city became a killing zone.

With pockmarked walls and shells of bombed out buildings such as the once majestic neo-Moorish Hotel Neretva (built in 1892) and the haunting nine-storey concrete skeleton of the former Ljubljanska Banka, most of Mostar looks as though it was kicked in the teeth.

Small cemeteries congested with white-marble tombstones abound. Closer inspection reveals that most died in 1993, 1994, or 1995. According to Pelko who lived through the war, snipers would pick off anyone walking down the street – “women, children, they didn’t care”. Sometimes bodies were left rotting for days on end along the main boulevard.

Today, sizzling in the late summer sunshine, the cobbled streets of the medieval Ottoman Old Town seem picture-perfect and peaceful. However, walking shoes are essential. I nearly broke an ankle teetering over the cobbles in high heels.

Here, as in Sarajevo, entrepreneurial coppersmiths have twisted spent ammunition into intricate sculptures and beaten shell casings into pens, sold at many souvenir stalls.

Accommodation varies from backpacker hostels to mediocre hotels but what Mostar lacks in luxury, it makes up for in historical interest, being a sobering snapshot of war’s inhumanity.

- Caroline Hurry flew to Copenhagen with British Airways, hired a car from there and drove to Bosnia with her husband.